Over the last 12 months we’ve run and reported on a series of experiments to identify the effect the Enervee Score has on influencing consumer preferences for more energy efficient products. In short, the Enervee Score seems to work well and we’re confident it’s a significant decision aid for driving better purchases — more energy saved, and less money spent.

However, these experiments have been run on a single product category — washing machines. As well as the obvious category-level limitation (does the Enervee Score work beyond washing your clothes more efficiently?), there’s a more subtle consumer behavior question to ask: does the Enervee Score work effectively when a different choice model for the consumer is being used?

By choice model, we mean the process by which we as consumers choose. Broadly, there are three choice models available: affect, attitude and attribute. Affect describes when we have an overall emotional response to an option. This may be driven by imagining using the product, and how it makes us look or feel. Affective choice models are typically salient when the motive to use product in question is consummatory i.e. the product is intrinsically rewarding to use (it’s a cliche, but the choice model used to choose an iPhone is likely affective). Alternatively, an attitude-based choice model uses overall views or attitudes towards the product in question. These attitudes may well be shaped by the brand. In the absence of affect, an attitude-based choice model is typically used when it’s difficult to compare products, and when there’s low involvement in the decision (let’s get this done). Finally, an attribute-based choice model involves us picking through specific attributes of the product before deciding (although we won’t weight these attributes equally). We typically engage in attribute-based choices when we’re highly involved in the decision and when there are plenty of attributes to distinguish between product options.

We’re pretty sure the choice model used by consumers to buy different home products and appliances, will be different. So far, we’ve tested the Enervee Score on white goods (washing machines), which will likely fall into an attitude-based choice model. But would it also work in an affective decision context? In other words, when a consumer is excited about the product — about using the product — would providing relevant energy efficiency information (in the form of the Enervee Score) still influence purchase preferences?

The answer is yes.

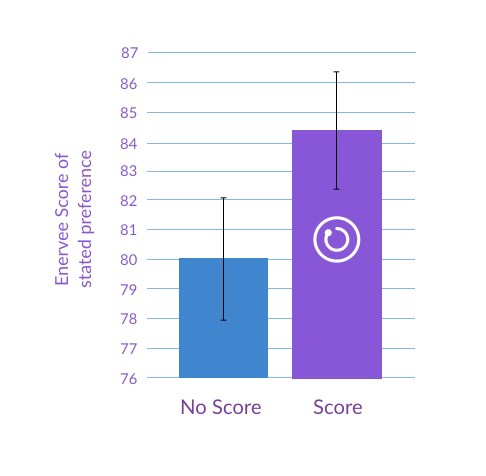

Once again, we see the Enervee Score makes a significant difference to the stated preferences of consumers when choosing a new TV.

This is good news. Even with a more emotional, high-involvement consumer decision, we can see the Enervee Score makes a difference to shifting preferences. This is an important result, as it gives us confidence that the Enervee Score can remain a valuable and salient decision aid across the full array of choice models we use as consumers. In other words, the Enervee Score is more than a steer when the purchase is perfunctory and low-involvement.