Over the last 12 months we’ve run and reported on a series of experiments to identify the effect the Enervee Score has on influencing consumer preferences for more energy efficient products. Using a mock-up of our lead product, Marketplace, we’ve seen the Enervee Score consistently deliver a shift in preferences (a good shift), including looking at consumers on low income.

In short, the Enervee Score seems to work well and we’re confident it’s a significant decision aid for driving better purchases — more energy saved, and less money spent.

However, these experiments have been run on a single product category — washing machines. As well as the obvious category-level limitation (does the Enervee Score work beyond washing your clothes more efficiently?), there’s a more subtle consumer behavior question to ask: does the Enervee Score work effectively when a different choice model for the consumer is being used?

By choice model, we mean the process by which we as consumers choose. Broadly, there are three choice models available: affect, attitude and attribute. Affect describes when we have an overall emotional response to an option. This may be driven by imagining using the product, and how it makes us look or feel. Affective choice models are typically salient when the motive to use product in question is consummatory i.e. the product is intrinsically rewarding to use (it’s a cliche, but the choice model used to choose an iPhone is likely affective). Alternatively, an attitude-based choice model uses overall views or attitudes towards the product in question. These attitudes may well be shaped by the brand. In the absence of affect, an attitude-based choice model is typically used when it’s difficult to compare products, and when there’s low involvement in the decision (let’s get this done). Finally, an attribute-based choice model involves us picking through specific attributes of the product before deciding (although we won’t weight these attributes equally). We typically engage in attribute-based choices when we’re highly involved in the decision and when there are plenty of attributes to distinguish between product options (think buying a car).

Why have we just detailed these different choice models? Because we’re pretty sure the choice model used by consumers to buy different home products and appliances, will be different. So far, we’ve tested the Enervee Score on white goods (washing machines), which will likely fall into an attitude-based choice model. OK, for some folks it may be an attribute-based choice model. But we’re pretty sure that no-one deploys an affect-based choice model for buying a washing machine.

This means we’ve so far tested the effectiveness of the Enervee Score in an attitude or attribute based decision context. So would it also work in an affective decision context? In other words, when a consumer is excited about the product — about using the product — would providing relevant energy efficiency information (in the form of the Score) still influence purchase preferences?

To test this, we decided to run an experiment using the one product category on Marketplace that we feel falls into this decision-making context: TVs. People are genuinely excited about buying and using a TV, and with the device sitting front and centre on our homes, the purchase becomes even more emotional. Plus looking at the marketing spend and creative used to build TV brands, it seems the manufacturers also think we use an affect-based choice model to buy our next TV.

Once again, we created an experimental version of Marketplace for a specific selection of TVs taken from the live Enervee Marketplace. Respondents were given the cover story that we were road testing a new shopping platform, and they were told they were to imagine they were in the market to buy a new TV. Once they’d used the platform (for as long as they wanted) they were then asked to select the TV they would prefer to buy from all those available on the site.

And once again, we manipulated the experience so that respondents were in one of four conditions: Enervee Score (yes/no) and Energy Savings (yes/no). When these variables were absent, we inserted dummy variables to ensure the overall experience was similar in terms of potential content across all of the conditions. This gave us a 2x2 factorial design, with the dependent variable of product choice, and a sample of N=209.

Results

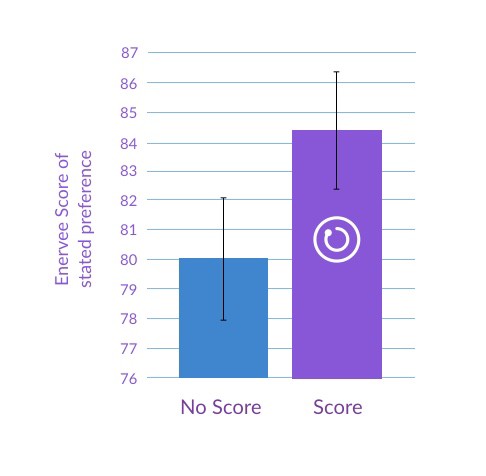

Once again, we see the Enervee Score makes a significant difference to the stated preferences of consumers when choosing a new TV (F=3.76, p=.05). Without the Enervee Score, the average efficiency of the TV being selected has an equivalent Enervee Score of 80, compared to when the Enervee Score is shown with 84.4 (see below).

This is good news. Even with a more emotional, high-involvement consumer decision, we can see the Enervee Score makes a difference to shifting preferences. This is an important result, as it gives us confidence that the Enervee Score can remain a valuable and salient decision aid across the full array of choice models we use as consumers. In other words, the Enervee Score is more than a steer when the purchase is perfunctory and low-involvement.

We’ve discussed at length that the Enervee Score may represent a nudge in certain buying conditions which switches on some version of the affect heuristic, based on the anticipation of feeling good about making the purchase. With TV choosing also using — to some degree at least — the affect-based choice model, this may explain how the Score performs in this context. This also bodes well for when Enervee launches its score in the product category probably most famous as relying on us using an affect-based choice model: car buying.

Of course, it’s true to say that when we make decisions about what to buy, we most likely flip back and forth across these different choice models at different stages of the decision-making process. What’s encouraging about the results we’re reporting today, is that it looks as if the Enervee Score can remain a valuable decision aid and energy saving nudge, irrespective of where in the journey and which choice model is being deployed.