In our most recent studies, we found that some out-of-date intuition is still alive and well in consumer decision-making when it comes to buying energy efficient products. We found a significant link between price and efficiency; that we as consumers think that energy efficient products are more expensive, and that the more efficient appliances will cost us more.

As discussed, this is useful to know, not least because it may well get in the way of us buying more efficient appliances for our home — we decide not to, simply because we think they cost too much in the first place. This is a clear example of where intuition interferes with the right decision. Somewhere in our dim collective past, we’ve clearly built the association that efficiency costs, but it’s simply not the case today.

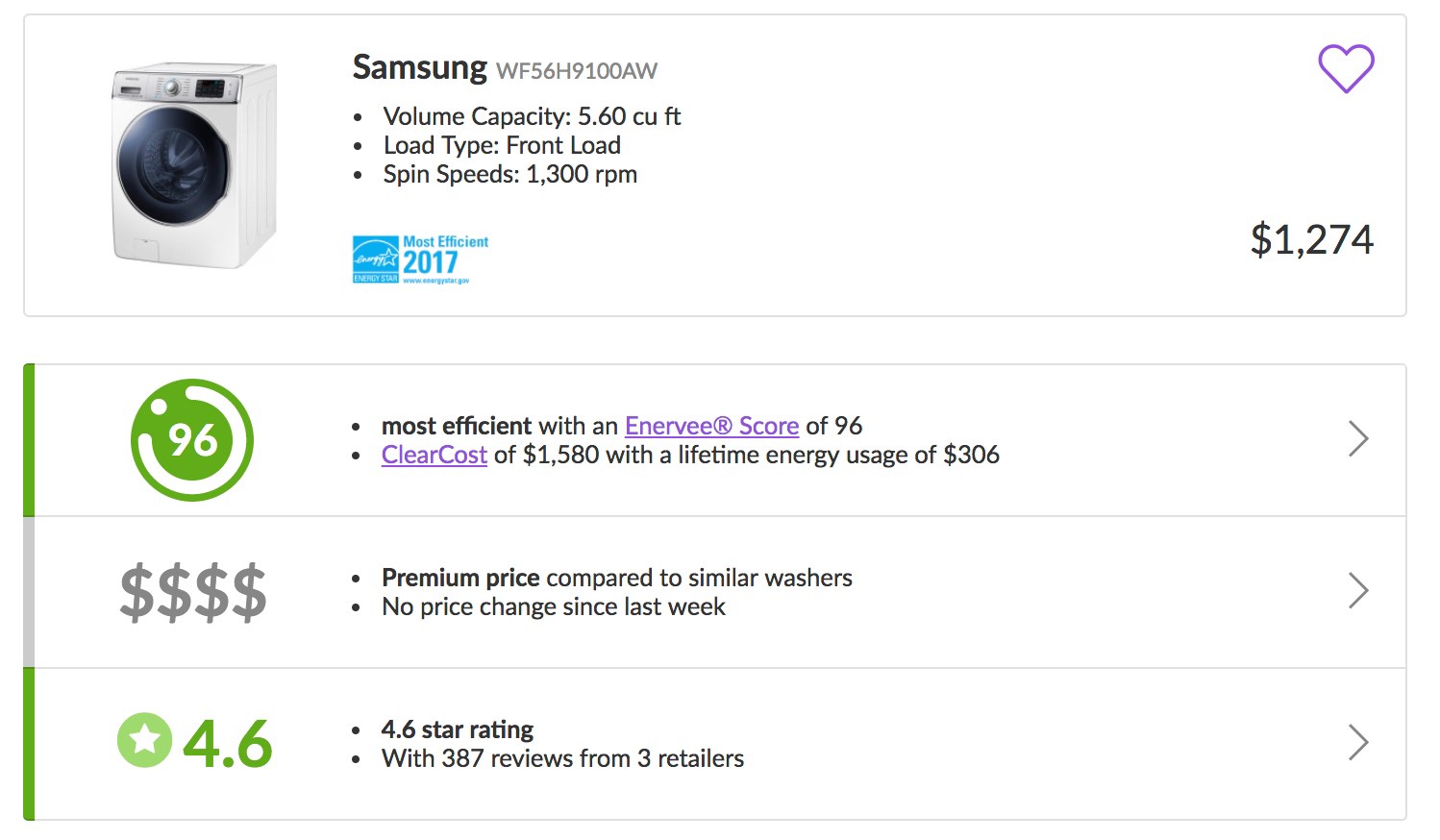

Recognising this ‘lay theory’ effect, we then ran experiments to show if presenting us as consumers with a summary piece of information that compared and loosely ranked the purchase price of the product in relation to relevant others (what we call ‘price worthiness’) could be enough to switch it off. In other words, if this price worthiness cue (based on a simple dollar scale ($-$$$$) could break our intuitive response that price and efficiency are linked.

The answer was yes — giving the decision-maker this small piece of information is enough to override our intuition, and switch-off this belief that if it’s efficient it’s got to cost more, and if it’s more expensive, then it’ll also be more efficient. Again, this is important, as it shows a simple intervention early in the decision-making process (e.g. when we as consumers are initially filtering or sorting product options before a deeper dive) can keep highly efficient products and appliances in our consideration set: efficient products rightly make it to the next stage!

But turning off a lay theory and knocking out its influence on our decision-making comes with added consequences.

Intuition can be considered a mental short-cut, or a ‘heuristic’. Its very purpose is to help us make decisions faster and with less cognitive effort. We often work hard to post-rationalise our intuition or gut feeling, but the reality is the initial feeling or response comes effortlessly. This form of decision-making can be described variously as System 1, hot, or peripheral[1]. But when we turn it off, we revert to a more cognitively demanding decision-making or processing style: deliberative, reflective, central or System 2. When we engage this style of processing, we are more likely to look at the details, challenge the arguments and come to a more measured conclusion before acting. In other words, it’s a very different way to make decisions — one that is more challenging of the information presented with which to make the decision.

This may have an impact on efficient purchases, in that if we as consumers are being told that the link between price and efficiency is not necessarily the case (despite our intuition previously telling us the link exists), this may override our heuristics-driven decision-making mode, and switch-in instead the more deliberative processing. This in turn would then push us to seek out further support for the (new) argument that we can get a new, fantastically efficient appliance for less money than we originally thought. The obvious place to get that support that the appliance we’re looking at is indeed a good one, is via consumer reviews. In other words, if the reviews for the product are good, then this would assuage our freshly-activated critical concerns that the product we’re looking at is a dud(based on the fact that it appears to be betraying our long-standing lay theory that you cannot buy a highly efficient appliance without paying a huge amount of money).

So we propose that a by-product of switching off a lay-theory is that consumers will become more reliant on consumer reviews for the product in question, looking to those reviews to further convince themselves, via a more critical, involved style of decision-making, that it’s OK to discount their efficiency-price lay theory on this occasion. In other words, reviews become a more important aspect of decision-making.

Experiment #1

To test this, we re-ran a version of our study design from the previous paper. Specifically, we presented consumers with four combinations of products based on price (high/low) and level of efficiency (high/low), giving us another 2x2 design. We also included a section on the product page which showed the number of reviews available for that product (from various retailers that stocked it).

After looking at the machine, respondents were then asked two questions about the reviews: 1) how important reviews were in making their choice for a machine such as this, and 2) how many reviews would they typically take a look at before deciding to buy a machine like this.

When we look at the results, it looks as if we as consumers do as we predicted.

The washer that had a high price and and high efficiency score prompted consumers to be significantly less reliant on reviews than when the machine has a low price but an equally high efficiency score.

In terms of the importance of reviews, consumers felt them more important when the price was low and the efficiency high (m=5.8 vs m=5.4; F=1.52, p<.05). They also proposed to read more reviews when the efficiency-price link was not in place (m=6.4 vs. m-7.02; F=1.47, p=.05).

In other words when the information betrays our intuition regarding energy efficiency and price, it looks like we become more reliant on others — in this case, the reviews of others — to support our now more critical decision-making style.

This is important to know. It means that if we want consumers to accept energy efficient products needn’t cost more, we need to bolster the buying experience at that time either with easy to access reviews, or easy to see review summaries.

Over the last two sets of studies, we’ve confirmed an intuition bias still exists when we as consumers think about energy efficiency and price — in short, the more efficient it is, the more expensive we think it is, and vice-versa. This is not true, and is not good, as it likely means many of us are sailing past great decision choices in terms of price and efficiency, simply because we don’t think they can be great choices.

So putting efficiency and price right next to each other is a good thing. We’ve also seen that if we know how the product we’re looking at (with its efficiency) rates on price compared to other similar products, this can disable this intuition and remove the bias. With this information, we accept efficiency doesn’t necessarily have to cost.

But nobbling this outdated lay theory does come with a price; it switches our decision-making onto a more systematic, deliberative mode. This means we look to validate our decision more carefully, and in this case check to make sure that we’re right to abandon our intuition that efficient products cannot be competitively priced. To satisfy this need for more information to confirm we’re making the right decision, we’ve seen providing reviews does the trick.

So it would seem three things are needed to help consumers make better buying decisions when it comes appliances and products for their homes:

- An easy to process energy efficiency score alongside the price,

- A clear indication of how that product compares to other similar products on price, and

- A straightforward snapshot of what others think of the product, via reviews.

These results support our decision to include these exact pieces of information next to every product, in every category on Enervee Marketplace, and to update every day where necessary. These are key interventions to encourage us as consumers to make better choices — choices we most likely want to make for ourselves and our families anyway, but that are being hampered sub-consciously by out-dated lay theories floating about like bad bits of old code. The good news, is that it seems we can flush that bad code out for good with a few simple (and sophisticated) interventions.

Enervee is committed to change the way we buy, and a key part of the journey is to make it easy to discount and let go of out-dated and potentially destructive lay theories.

Notes:

[1] We’re being a little loose here — these three decision styles are not strictly interchangeable, as they have different conceptual foundations, and apply to different decision or behaviour contexts. However, they all refer to a more superficial, impulsive decision-making style.