It makes so much sense. Buying energy efficient products. Lower running costs — thanks to higher efficiency — mean we end up paying less over the lifetime of the product. What’s more, even if the purchase price is a little higher than the less-efficient alternative, there are often hefty rebates kicking around, which means we don’t even have to pay more at the outset. It should be so simple. Yet, we still tend to opt for the less efficient option.

In previous posts, we’ve shared the results of experiments we’ve run at Enervee that show real promise in getting us all to make more efficient choices. We’ve shown that our proprietary Enervee Score, which ranks all products on a scale of 0–100, makes a significant (and positive!) difference to the products consumers choose within stated preference studies. And we’ve also seen that our customized energy savings predictions — that show what you’d save by buying a specific energy efficient machine compared to the average machine in its class — can also drive more efficient choices, under certain conditions.

Hold on, under certain conditions? To be precise, we’ve found the energy savings information — in the form of dollars saved — influences decisions with financially-stressed shoppers and leads to better choices. This makes sense — if we’re concerned about money and it’s top of mind, it’s very likely showing us a personalized projected dollar saving from an energy efficient purchase will make a difference and influence our preference. In this instance, energy savings in dollars becomes salient as an attribute or characteristic that steers our choice.

But that’s the only condition under which we see this piece of information (shown as a simple piece of arithmetic) making a difference. Which raises the question: can we make the dollar amount of energy savings salient for everyone? If we could make that happen, it would be another lever at our disposal to nudge, jolt or engage people to buy energy efficient.

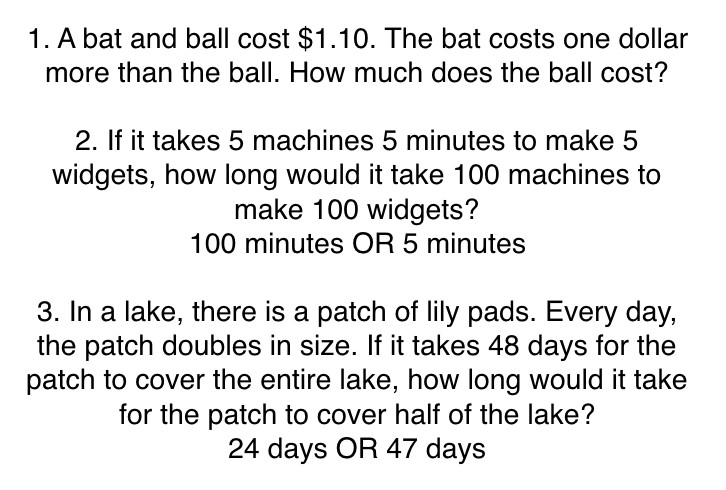

How might we do that? One idea comes seemingly from a left-field area of research within psychology: fluency. To explain this better, take a look at these three mental puzzles, and quickly jot down your answers to each one.

All done? Great. We’ve put the answers at the bottom of this post. How did you do?

If you got one or more of them wrong, don’t worry too much. In the many many times this study has been run, typically more than 90% of respondents get at least one wrong.

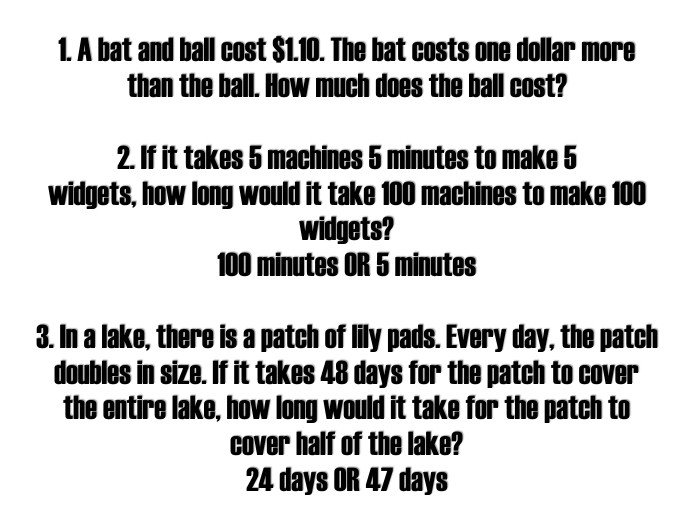

But here’s a thing. Look at the same questions again, but this time in a font that is harder to read.

When people see the questions — the same questions, remember — written like this, guess what? The error rate falls to 35%. The same questions, and — to all intents and purposes — the same people answering the questions.

This is a ‘disfluency effect’.

As the name suggests, disfluency is the opposite of fluency, and describes the ease (fluency) with which we can process information.

The font used in the second version of the mental puzzles above has been found to be a highly disfluent font (it’s Haettenschweiler, in case you’re interested, whereas the font in first case is Helvetica — a hugely popular font specifically because it is so fluent). Why does a disfluent font have this effect? Because the very fact that it’s hard to read means we cannot try and solve the puzzle with a cursory glance, with us instead having to concentrate on the information. This in turn activates our more deliberative, ’System 2’ thinking mode, which is the more processing-happy mode. And when that mode is active, our increased processing ability means we tend not to be caught out by the questions.

So if changing the font is enough to get people to make fewer mistakes with a series of simple mental puzzles, could doing the same thing be enough to get us to do the sums correctly with respect to energy efficiency savings?

The answer would be appear to be yes. In our study, changing the font to one that is disfluent led to more efficient choices being made.

In other words, we find support for the argument that making energy efficiency less fluent — in terms of the dollar savings calculation from a more efficient purchase — causes us to focus and process the information more carefully, which in turn causes us to ‘recognise’ the financial argument for making a better buying decision.

Counter-intuitively, increasing disfluency leads us to do the math right when it comes to understanding the benefits of buying energy efficient.