As energy efficiency policymakers, regulators and advocates, we are continually faced with the question of how to accelerate and scale private investment into commercially available energy efficient technologies and practices. The raw numbers on payback periods are often used to argue that there’s pervasive “underinvestment” into cost-effective solutions.

One common strategy in the consumer product space is to invest public money into marketing, education and outreach (ME&O), the premise being that if people only understood all of the benefits of energy efficiency — such as the life-cycle cost benefit of spending more on an efficient product now to save more on energy bills later — they would purchase more efficient products, even if they came with a higher price tag.

The problem with this strategy is that people don’t always behave as the efficiency policymakers expect them to. On the one hand, lower income households may simply not have the luxury of paying more now for benefits down the road. It is critical to target such financial barriers with other instruments, such as consumer credit or on-bill repayment.

More broadly, even when presented with lifecycle cost information, shoppers most likely will still choose to ignore it, for a number of reasons (not least because lifecycle cost represents yet another attribute to consider in an already complex decision, and we tend to chronically over-discount future savings to the present day, thus reducing the “saving” to something almost imperceptible today). Faced with what can often feel like stubborn obstructions to consumers making better choices, the energy efficiency community could well benefit from decision and behavioral science insights.

If you think about it, it’s understandable why we ignore energy bill savings in many cases.

When you’re shopping for a tablet, and the maximum energy bill savings amount to only a few dollars per year at most, for example, why bother to consider this attribute, when there are others that may be far more important to you, such as battery life, look & feel or computing power? This is backed by academic research demonstrating that more choice, in terms of features or attributes, can decrease cognitive ease in the decision making process, pushing us back to making a decision based on just one or two features we’re already comfortable with (such as price or brand).

Even in a case like water heaters — where the energy bill savings can run into the hundreds of dollars per year — if it’s difficult (or impossible) for the shopper to compare savings across the models they’re interested in, they’re likely to exercise what is termed “rational inattention”: They choose to ignore the energy dimension entirely, because it’s simply not worth their effort to do the necessary research to make an energy-smart choice (the same logic applies to the tablet purchase).

One response to try and offset these myriad challenges has been energy labels, but they have limitations, such as a lack of granularity, or an inherent inability to present information that is personalized for the individual.

Another example is when a consumer has his/her heart already set on a certain product that just happens to use a lot of energy, such as a TV with 4k resolution, or a powerful sports car. In these cases, consumers may well deploy a predominantly attitude-based choice model, so getting them to think about a specific — and new — attribute (energy efficiency) is a tough sell. Some folks may be swayed by energy efficiency messaging, but it’s the hot, new premium products and clever services of the future, designed from the outset with sustainability in mind, that could become the coveted status symbols of younger generations and drive mass fascination with cleantech.

But we cannot afford to wait. Americans purchase tens of millions of consumer electronics and appliances annually, including 35 million televisions. These 1-time purchase decisions have a lasting impact on the nation’s energy demand. Take televisions as an example: TVs consume an astounding 7% of national purchased electricity in the USA, and TV and other consumer electronics electricity demand is expected to grow further. Enervee data for the US market show that the most efficient TVs (with Enervee efficiency scores of 90+) use 40% less than the market weighted average for new TVs. We need to capitalize on these opportunities.

Beyond overt “energy education” then, what can be done to trigger energy-smart purchase decisions and capture the sizable savings beginning today?

Fortunately behavioral science offers proven strategies from other fields like public health and consumer choice that are beginning to be applied in the energy space.

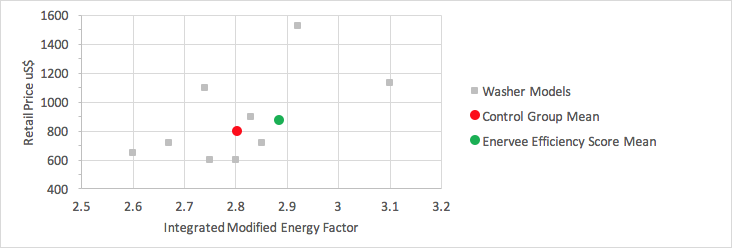

We recently conducted an experiment with a random sample of 200 people in the USA to find out whether the availability of two pieces of energy information influenced their clothes washer purchasing decisions (Champniss & Arquit Niederberger, in press). One was estimated energy bill savings, and the other was a relative Enervee efficiency score, presented as a numerical rating on a zero to 100 scale, with 50 being the floor for new products currently offered for sale, and the most efficient products assigned scores near 100.

We found that the availability of the energy bill savings information had no effect on the energy efficiency of the washers the test subjects selected — more about this result later — but the Enervee efficiency score did.

When test subjects were exposed to the Enervee efficiency score, their top washer model choice was 2.9% more energy efficient on average than when neither the score nor the energy bill savings were provided*, despite the fact that the retail price of the two most efficient models were the highest among all 9 models in the experiment. It’s worth noting that we found no pro-environmental bias among the participants assigned to any of the four treatment groups.

Given that the total range in our efficiency metric was 19% across these washer models (IMEF between 2.6 and 3.1), a 2.9% more efficient choice in terms of IMEF on average is 16% closer to the unlikely optimum, if all respondents were to select the model with the highest efficiency. This would be unlikely for several reasons; for example, this model was the largest (with a drum size of 5.6 cubic feet) and came with the second highest price tag (which, at more than $1,100, was nearly twice the price of the least expensive models in the experiment).

The numbers may not impress at first glance, but here are four things to consider:

> The clothes washer Federal test procedure and energy conservation standards, as well as the ENERGY STAR qualification criteria, were updated in March 2015, effectively narrowing the range in consumption across full-size washer models to roughly 170 kWh/y to 85 kWh/y.

> The choice set of washers included in our experiment was restricted to front-loading washers (with a maximum annual energy consumption of 135 kWh/y), and was consequently skewed toward the more efficient end of the market (top loading machines are subject to significantly less stringent requirements).

> The electricity consumption of the washer is only a small part of the energy required for a load of laundry. Far more energy is needed to heat the water used by the washer and to remove the remaining moisture from the clothes after the wash cycle than is used to power the wash cycle. For the washer models in our experiment, the total energy requirement is a factor of 4 higher than the machine energy consumption alone. Thus a 2.9% improvement in IMEF can translate into much larger energy savings than one might think (unless you use exclusively cold water wash and line dry your clothes).

> Based on our experimental results, these savings may well be achievable with no investment in overt energy education and no financial incentives.

In contrast, providing information on energy bill savings had no influence on the efficiency of consumer product choices. This should not be taken as a definitive result; rather it may merely reflect one of the shortcomings of our experiment, namely that we did not offer participants the option of customizing the bill savings estimates to accurately reflect their own personal situation (e.g., energy tariff, number of loads per week, fuel type for water heating). As mentioned above, this corresponds to one of the main shortcomings that can limit the impact of label schemes. We’re eager to find out if daily updated and personalized savings estimates will yield better results.

One of the most enlightening (and exciting) aspects of the study is that participants did not even perceive the new shopping site they were presented with as providing information on the energy efficiency and running costs of washing machines.

This is actually great news for those who want to transform markets and speed private investment into energy efficiency, because it suggests that rational inattention can be addressed effectively by integrating energy information into the shopping journey in such a way that consumers don’t have to actively think about it.

We don’t yet know if this will work across all product categories (we plan to test more in the coming months), but it certainly seems promising for appliances, light bulbs and HVAC (heating, ventilation & air conditioning) equipment.

Notes

*The energy efficiency metric we used was IMEF (integrated modified energy factor), which is the quotient of the capacity of the clothes container divided by the total clothes washer energy consumption per cycle (=machine electrical energy consumption + hot water energy consumption + energy required for removal of remaining moisture in wash load + combined low-power mode energy consumption). All results presented in this blog were significant at the p<.01 level, unless otherwise stated.