Last month we shared the results of a study we ran with Enervee Marketplace, to better understand and test the effects of the platform on nudging people toward making more efficient product purchases. The results showed that our Enervee Score — as a clear 0–100 score for every product — consistently drives visitors to make significantly more energy efficient preferences — 15%-20% more efficient, to put a number on it. You can read the full piece here, if you’re interested.

However, when we ran that study, we knew the design would not answer one of the most hardy of questions posed by critics of driving more energy efficient behavior: isn’t saving energy and the environment reserved exclusively for those who have the lifestyle and money to care?

Put another way, can people who are on low incomes, with tight budgets and probably thinking more day-to-day, also afford to make energy efficient choices when replacing appliances for their homes?

To test this, we re-ran our exact same study but chose a sample of active US consumers who were on low salaries and who had previously been identified as of low socioeconomic status. We were interested to see if our two key pieces of information presented on Marketplace would make a difference to preferences for this group. To recap, those two pieces of information were:

- The Enervee Score — our 0–100 scoring system to show relative energy efficiency of the product compared to all others in the product category,

- The Energy Savings — a detailed estimate of potential financial savings to be made by buying that product compared to a product of standard efficiency in the product category.

Once again, we created a controlled version of Marketplace featuring a selection of washing machines, and manipulated respondents’ access to one of four variations of the site: Enervee Score (yes/no) and Energy Savings (yes/no). We also once again measured if respondents felt the platform was overtly pro-environmental and energy saving in its design, and what their general views were toward the environment (based on a tried and tested scale).

The results both support the earlier conclusions and reveal the potential for Marketplace to operate on multiple levels for different types of appliance shopper.

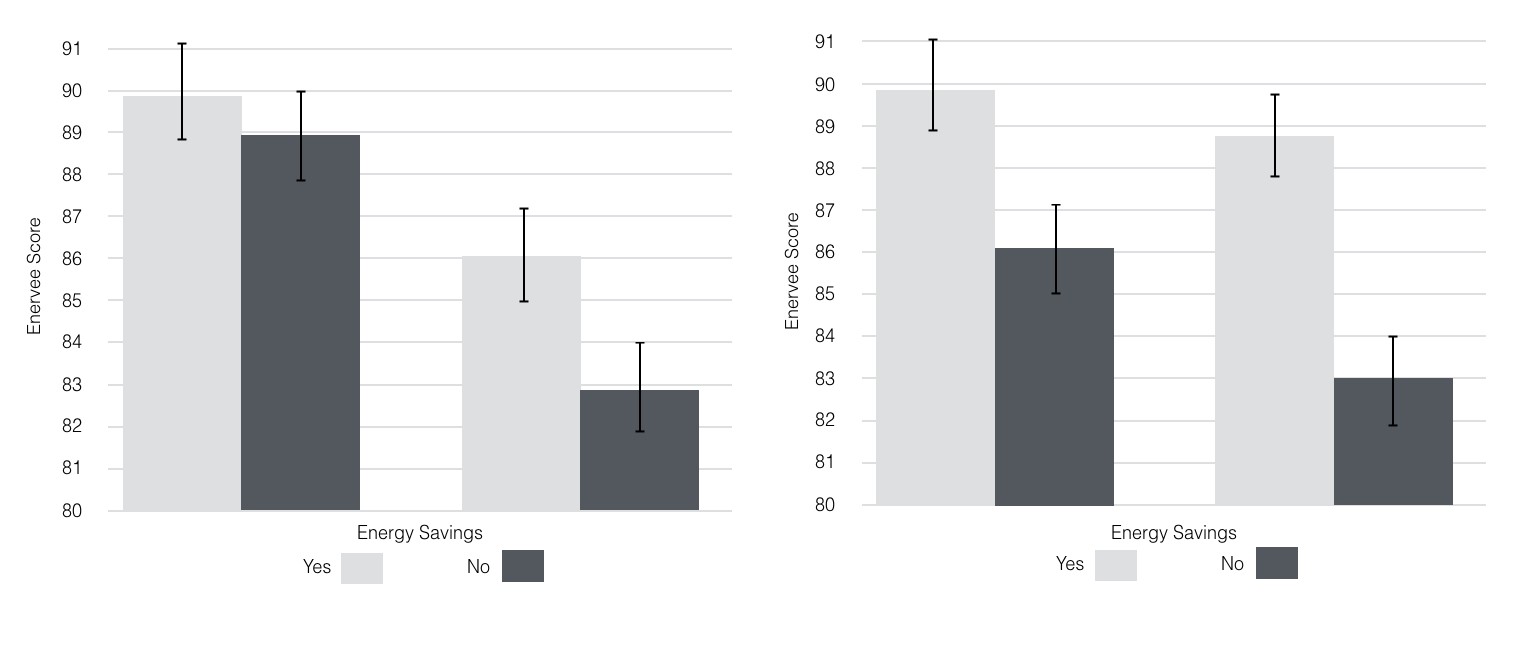

Once again we see the significant effect of the Enervee Score nudging people toward making more efficient choices. Whether recording their first choice for a new machine, or aggregating their top three choices, when the Enervee Score is present on the platform, low-income respondents steer themselves toward significantly more efficient products. In fact, the effect is slightly larger with this group than with the original group (see below).

However, this second study also revealed something interesting with respect to the Energy Savings function and its potential influence on making more efficient choices. Whereas in the first experiment (without the required no low-income skew), the Energy Savings function had no effect on making more energy efficient choices, in this second experiment, it looks like it does. Looking at the first choice of washing machine, its effect is marginally significant, suggesting that with a larger sample of users, we’d secure a clear effect. And looking at the aggregated first three choices, we already see a significant effect of the Energy Savings function on making more efficient choices.

At first glance, this would make perfect sense. For more financially sensitive shoppers (who made up our second study), it seems sensible to take hard financial benefits (lower outgoings) into consideration when making a new appliance purchase.

Previous research has shown that for those who consider themselves as having little money or under financial pressure, any piece of communication that discusses money (whether it’s coming in, or going out) results in those individuals focusing on the financial elements of that communication. This could explain what’s happening here — whereas the broader user group (study 1) seemingly glossed over the financial argument presented by the Energy Savings (resulting in no effect), this second group is naturally drawn to this argument, due to their general situation. Further support for this argument is seen in the questions we asked at the close of the study. Whereas in the first study there was no effect of the score and savings functions on people’s perceptions of the energy saving positioning of the platform, in this second study, once the energy savings information was in play, respondents saw the platform as significantly more pro-energy savings in its positioning. Again, with financially sensitive consumers already drawn to the financial argument to buy energy efficient via the energy savings function, it’s no surprise they carry that focus through to perceiving the platform as a whole to be pro-energy saving.

However, the story’s not over yet.

If we poke around the results of this second study in a little more detail, we also see there is no interaction effect. An interaction effect describes when two variables combine to affect each others’ outcomes. In this case, it would be a fair argument to say that the Energy Savings and the Enervee Score should combine forces to deliver the strongest effect in terms of shifting preferences toward energy efficient options.

But we don’t see it (we didn’t see it in the first study either).

So whilst Energy Savings has an effect on its own with this low-income group, it does not double up with the Enervee Score to boost the effect. Why would this be? Well, there’s one explanation that is, we think, both the most interesting and the simplest. There is no interaction effect for the simple reason that each of these functions delivers its result by means of a different underlying psychological effect.

For the Enervee Score, we’d argue the result driven by a social status effect. After all, the Enervee Score not only signals the efficiency of the machine you’re choosing, but also the efficiency of your decision. In other words, it says something about you as an individual. This effect — referred to signalling — is well documented, and has been used to explain the huge success of Toyota’s Prius (the signalling opportunity is considerable with a Prius as it can only be a hybrid). We can call this motivation an impression management motivation i.e. it makes us look good.

But for Energy Savings, this financial result is something that no-one else can see — no-one knows that your machine is saving you a dollar amount per month, as its day-to-day cost is invisible to everyone but you and your wallet. So the incentive to engage with this feature is more likely based on more profound personal circumstances rather than social status. In this case, the motivation can be called intrapsychical i.e. we don’t really care if other people do or don’t care.

The argument that these features trigger different underlying mechanisms is further supported if we think about the different forms a behavioral nudge can take. On the one hand, we can have a nudge intervention that activates a heuristic (a mental rule of thumb, or short-cut). The Energy Star label can be thought of as nudge to switch-on a heuristic, as it provides a valid short-cut to making an energy-efficient decision, and it’s feasible the Enervee Score could be doing the same, in the sense that it activates a heuristic to ‘simply’ look for the highest score (in that respect, we’d argue it’s a more effective heuristic than a more standard label for energy efficient buying, as it not only provides a short-cut, but it also triggers a target effect, to try and get as high a score as possible).

An alternative nudge intervention, however, is to switch-off a heuristic and prompt the decision maker to think harder about a decision. This may well be what we’re seeing with the Energy Savings figure when presented to the low-income group; as money’s already a salient topic for these shoppers, providing a financial benefit of buying energy efficient prompts these shoppers to think more carefully about their choice, leading to more efficient selections.

It’s also worth reporting that, as with our first study, in this second, low-income study, we again saw no significant difference between groups across the conditions in terms of their pro-environmental leanings. In other words, once again we find support for our argument that the effects we’ve seen here are a product of the manipulations, not of underlying and pre-existing attitudes of the respondents.

So does Enervee’s Marketplace have the potential to nudge us toward more efficient behaviors via two different effects?

Very possibly. Probably, in fact.

We should, and will, test further. One such area will be trying to understand how to make the Energy Savings figure more salient for those who may not carry the same financial pressures as those in the second study — after all, everyone should like to save money. Whilst we speculated that the failure to see its effect in the first study may have been due to a lack of personalised feedback, the results from this second study open up the opportunity to try other routes.

One of these may be variations in fluency and disfluency for energy savings information on Marketplace as a means to switch off the heuristics-driven decision-making for visitors i.e. to nudge all groups to notice and process the financial benefits as much as it seems the financially-stressed do (see our thoughts on this possible effect here). We’ll report those results the very minute we have them.

But in the meantime, the results of this second study make for good reading — for us at least! We’ve more support for our argument that the Enervee Score does the trick in terms of nudging behaviors in the right direction, even amongst a target group for whom energy efficiency may not be the top priority. And we’ve also seen what may be the potential of the Energy Savings function to help drive that effect, albeit by a different underlying mechanism.

These are all valuable insights as we continue to move forward on our ambition to nudge us all toward making more energy efficient choices, whether these nudges involve the subconscious, the conscious, the emotional, the rational, the selfish, the altruistic, the social or the personal. Because we recognise there’ll be more than route to moving us all to buy energy efficient. And we just need to help everyone find their own way.