Encouraging us as consumers to save energy as we go about our day-to-day routines is a crucial piece of the wider energy puzzle that we need to solve. Residential energy usage accounts for over 20% of annual emissions in the US. Yet whilst there’s a clear incentive for us as consumers to engage in energy saving behaviors (doing so saves us money), other influences seem to frequently get in the way of these results. And even when many of us claim to hold energy saving attitudes, or consider protecting the environment important, such attitudes frequently whither in the face of actual behaviors. This issue is so well established, consumer psychologists refer to it as the ‘attitude behavior gap’.

One route to potentially get round this attitude behavior gap is to avoid attitudes altogether. In other words, rather than trying to prime or reform an existing attitude to hopefully elicit the (energy saving) behavior, we can go straight for the behavior itself. This is the basis for the wide body of work on nudges, which have been shown to be highly effective in getting us as consumers to engage en masse in behaviors that deliver welfare to us and society.

This is where Enervee enters the scene. We are trying to combine data, design and digital marketing with behavioral science to lead us as consumers to make energy efficient choices. We’re committed to nudging consumers to be energy-smart in their buying behavior.

But sometimes nudges fail to nudge. Or worse still, nudges inadvertently nudge in the wrong direction. Research has shown that whilst consumers generally respond well to nudges to save energy (‘how much are you using compared to your neighbours?’), this effect is very much dependent on the make-up of the sample: if the sample is Democrat, the savings effect is seen, but if the sample is Republican, not only is the savings effect not seen, but there’s an increase in energy usage.

One explanation for this misfire is that Republican-leaning consumers may feel the nudge takes away choice; that in being nudged toward one option, others are taken off the table.

This isn’t the case, however. A nudge — by definition — does not take choices away from the decision-maker. This is the basis of the term libertarian paternalism that Thaler and Sunstein use to describe the ideological underpinnings of the nudge: paternalism in the sense that the decision is made easier through the choice architects pointing us toward an optimal choice, and libertarianism in the sense that no choices are taken away.

And whilst it’s fair to say that the majority of nudges point toward the choice architecture being designed to encourage the easier selection of one option over others (i.e. gently pushing us toward a better choice), it’s also the case that nudges can work the other way. That is to say they can work to reveal the full range of choices available to the decision-maker, where we typically lunge for just one (for example, as a result of habit or cursory engagement with the decision). In other words, a nudge in this form is less about pointing toward one option, and more about reminding us that there are many options. In this capacity, the nudge works by getting us to stop and think again — to be deliberative where the decision is normally automatic.

Our recent paper on fluency may be a good example of a ‘think again’ nudge. With the font being difficult to read, the style of presentation of the energy saving information itself acts as a nudge to focus on the decision in hand, and to make a better (energy- and cost-saving) decision. In this case, the nudge is pulling us into thinking more about the choices available, in order to make a better choice.

Knowing that nudges can work both ways — in other words, not just respecting but actively leveraging both aspects of the ‘libertarian paternalism’ label — is the answer to getting the Conservative consumer to respond positively to an energy saving behavior nudge, to develop a nudge that allows that consumer to more effectively exercise free choice for a better decision? In other words, to pull more information towards them, rather than be pushed toward a better option?

This was the focus of this study — to see if the Enervee Score could be effective at steering more efficient choices, irrespective of political leaning.

To test this idea, we re-ran one of our earlier trials which was a choice experiment for a new washing machine.

So do Democrat consumers really feel differently about the environment than Republican consumers?

Yes.

And can Republican consumers engage in energy saving buying behavior as much as Democrat consumers?

Yes.

The results from the experiment itself make for interesting — and reassuring — reading.

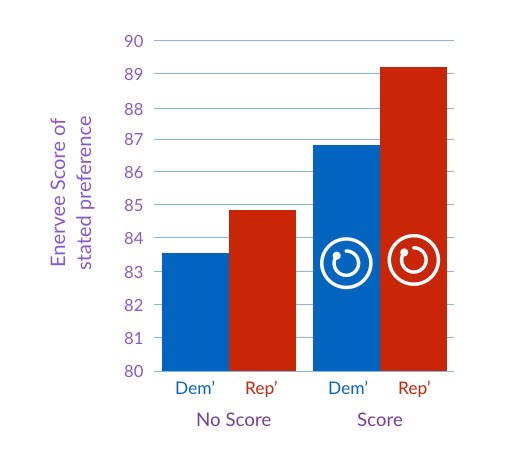

First, we see that in the conditions when the Enervee Score is present on Marketplace, consumers overall make significantly more efficient choices. In other words, the Enervee Score continues to influence preferences.

Second, we saw that there was no significant interaction effect between political orientation and the effect of the Enervee Score (F=.238, p>.1). In other words, political orientation has no significant effect on the power of the Enervee Score to move consumers toward making more efficient purchase choices.

This is a good result.

Where other nudges have been shown to fail when it comes to delivering energy saving behaviors across such groups, the Enervee Score keeps on delivering.